This article is based on a paper I’ve just had published in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics, available here.

Resale Price Maintenance (RPM) is an agreement between manufacturers and retailers, whereby manufacturers only supply retailers with their output, if the retailer agrees to sell the products at a specified price. There are a number of valid reasons why manufacturers and retailers would agree to such a restriction on behaviour. One example is that manufacturers might want to encourage retailers to offer promotional services, or help showcase the product (for example, offering test drives of cars, making nice stands to draw customers’ attention to the latest book, providing walk-throughs of the technical specifications of different laptops, etc). This is a lot harder to do if firms are fiercely competing on price. We can see this in action, where people go to a bricks-and-mortar shop to explore different product options but then buy the product online cheaper. The retailer which incurred costs, thereby having to charge a higher price to remain profitable, to provide the service to the customer lose the sales. In the long-run, this can be detrimental to manufacturers if retailers decide to stop providing this service provision and customers purchase less frequently without this information. Another argument in favour of RPM is that it can be used to remove double marginalisation. Double marginalisation occurs when both the manufacturer and retailer want to make a profit and so add a margin to the price of the product they sell. This means that consumers have to pay a margin to both the manufacturer and the retailer. One way to eliminate this double cost is for a manufacturer to impose an RPM which limits the ability of the retailer to add a margin, and then recoup the retailer’s loss through another mechanism (there are, however, other ways to eliminate double marginalisation, without relying on RPM).

However, RPM can also be used to facilitate collusive practices and increase retail prices to maintain higher monopoly profits (which can be shared with the retailer, to encourage them to participate in such agreements). Concern around these collusive motives for RPM has led to most competition authorities across the world banning RPM practices completely. This means that retailers are allowed to sell products at whatever price they want, without interference from manufacturers (except, in some cases, for the displayed information on recommended retail prices, RRPs, a cool paper which investigates those, and finds RRPs to be pro-competitive, can be found here).

Testing whether RPM is beneficial or harmful in practice is therefore very difficult. Some researchers have tried to examine the impact on retail prices, and quantities sold, using known evidence of illegal instances of RPM. This has the obvious detraction that only the worst cases (in terms of consumer outcomes) are usually discovered and prosecuted under the legal system. Such evidence would clearly be biased towards the worst outcomes. To provide alternative evidence on the effects of RPM, my research instead looked at a specific industry where RPM is actually permitted in some countries: the retail sale of books.

In a number of countries, RPM is mandated on the sale of books – publishers set a fixed book price (FBP) which retailers have to sell the book at. Motives for such a policy include the service provision argument made above, in addition to policymaker’s wishes to promote reading as a cultural activity, through the expanded promotions and presence of bookshops, as well as promote the language through publishing, which can be made easier with larger publisher profits to be used to finance a wider range of books (in theory, at least).

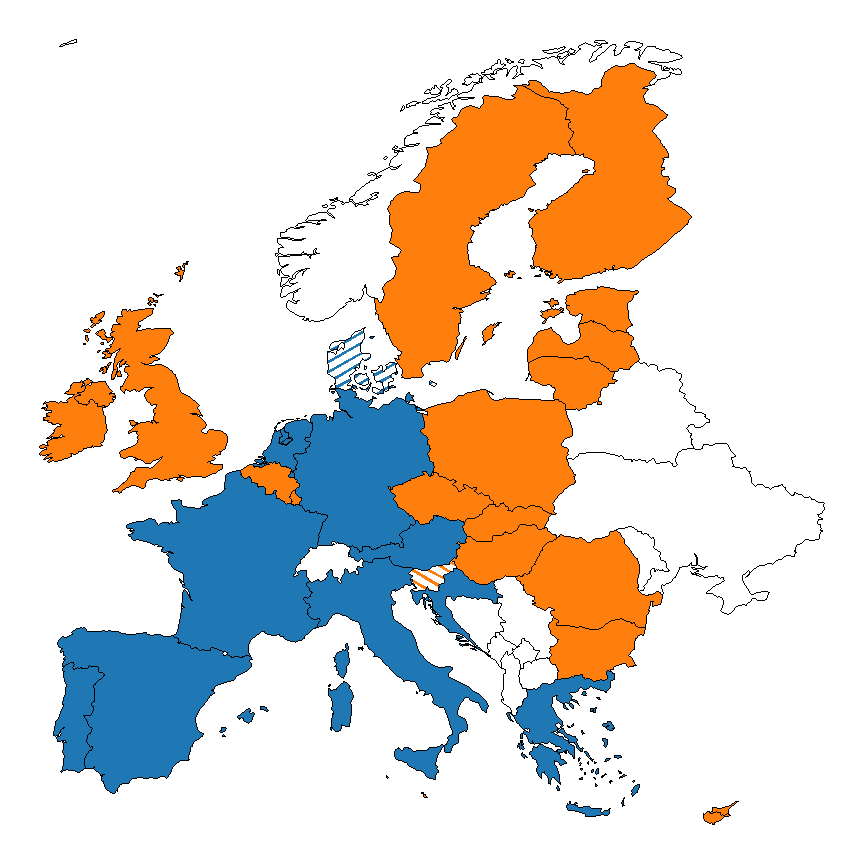

In my study, I compare the existence of FBP policies across Europe, looking in particular at countries which adopt or revoke such policies, to examine the effect on retail prices (of books) and on the amount sold. Consequently, I draw conclusions on the impact of RPM from these findings. From the map below, we can see that there are a large number of countries with FBP policies and several countries adopt or revoke throughout my sample period (2008-2019).

I use the econometric technique of two-way fixed effects (testing for any concerns related to staggered adoption) and find no evidence that having an FBP policy resulted in higher prices but that the quantity of books sold was higher in countries with an FBP policy. This seems a little odd, and contradictory to the theory. How can prices not be higher in countries with mandated RPM? I don’t have a definitive answer but turn to the vertical contracts literature, which points out that whether RPM prices will be higher or lower than non-RPM prices depends on the bargaining power between manufacturers/publishers and retailers. If manufacturers have high bargaining power then RPM prices will be lower than non-RPM prices, as manufacturers set prices optimally, removing double marginalisation, and lower consumer prices, to increase overall sales. I am able to do some indicative (but not definitive) tests to see whether this happened in my dataset, and the evidence points towards manufacturer bargaining power being higher in RPM countries than non-RPM countries, providing support for this hypothesis which could explain why prices are not higher in RPM countries. Furthermore, elimination of double marginalisation in RPM countries could explain why there is limited upward pressure on prices. Secondly, to answer why quantity sold is higher in FBP countries, I find that the number of bookselling firms is higher in FBP countries, suggesting that consumers have access to a wider range of firms, which, alongside increased service provision, can help to explain why the quantity of books sold is higher in FBP countries.

To sum up, I find that FBP policies result in a greater output of books being sold than in countries without FBP policies, and there is no impact on higher prices. Translating these results to the RPM debate, my findings suggest that in a certain industry, RPM has positive effects. Consequently, policymakers should maybe be more considerate towards the possibility that RPM can have positive implications. Nonetheless, this finding is limited to a single industry, which may not be representatitive of the effects of RPM, so I do not conclude that RPM should universally be permitted.

You can read more details about this in my paper here.