What were the causes of the distinctive characteristics of English fertility behaviour during the Industrial Revolution? (b) How did the fertility rate interact with economic growth during this period?

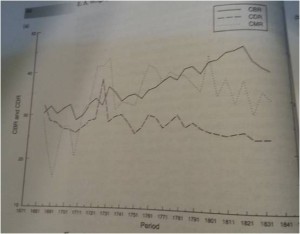

Before the causes of fertility behaviour are explored, we need to first look at what these characteristics were in the first place. From the graph to the left1 we can see that the crude birth rate (which is defined as the number of live births per 1000 people) starts off at about 30 births per 1000 people in 1680 but increases to about 44 births per 1000 by 1820. This is a significant increase, especially as Malthus believed that the maximum biological rate of fertility can only be about 50 per 1000 people – so the fertility rate was approaching the maximum in 1820.

Before the causes of fertility behaviour are explored, we need to first look at what these characteristics were in the first place. From the graph to the left1 we can see that the crude birth rate (which is defined as the number of live births per 1000 people) starts off at about 30 births per 1000 people in 1680 but increases to about 44 births per 1000 by 1820. This is a significant increase, especially as Malthus believed that the maximum biological rate of fertility can only be about 50 per 1000 people – so the fertility rate was approaching the maximum in 1820.

There are many different arguments for what caused this astonishing increase in fertility. The first such argument was that the average female age at first marriage fell during this period, from 25.8 years in 1680-9 to 23.8 by 1820-92. Such a decrease in the age of marriage would mean that a woman would have longer in her life to have more babies. This would be extenuated by the fact that at a younger age a woman is more fertile and is thus likely to fall pregnant more quickly than if she was older. In the period 1820-39 the average interval between births was 30.5 months3; hence a reduction in the age of first marriage of 24 months would mean that a woman would, in theory, be able to have an extra 0.79 babies in her life time.

It is also pertinent to note that the total marital fertility rates of women between the ages of 15-49 increased from 8.9 in 1680-1729 to 10.45 in 1780-18294, meaning that women in marriages were having 1.55 more children in the latter period than the former, thus increasing overall fertility rates. A reason behind this is that female nourishment increased through this period which meant that mothers ate a lot better; the result of this was that fewer women died from pregnancy, thus being able to reproduce again in the future leading to a higher fertility rate. Falling adult mortality in general “meant that more marriages lasted longer, increasing the overall number of children born”5.

This increase in nourishment was also significant in the fact that it resulted in fewer stillbirths because better nourishment in the mother fed on to better nourishment for the foetus causing an increase in weight and health. The increase in weight meant that there were more live births. Since fertility is defined in terms of live births a fall in the number of stillbirths would lead to a higher fertility rate.

To conclude, the main causes of English fertility behaviour during the Industrial Revolution were; a fall in female age of first marriage, accompanied by an increase in the fertility rates of married women and also to a larger extent the significant fall in stillbirths as a result of improvements in nourishment. There were many other causes which can be attributed to the changes in fertility behaviour such as a fall in the number of women remaining single through their life and an increase in fertility rates of unmarried women, which increased the birth rate by about 4.7% over the given period, but I don’t believe these causes to be as significant as those already discussed. Some have also argued that Britain’s population in the 18th century still hadn’t recovered from the Black Death in 1348 and that the increase in fertility was just Britain catching up with the rest of Europe, but this is a contentious issue which doesn’t have general agreement on.

The interactions between the fertility rate and economic growth work in both directions, i.e. fertility rate is affected by economic growth but it also affects the level of economic growth, and the mechanisms for this will be explained below.

Firstly, let us look at how the fertility rate is affected by economic growth. We have already seen that one determinant of fertility is the female age of first marriage and this itself is heavily influenced by real incomes. In England in the 17th Century marriages were largely consensual and initiated by the parties involved, as opposed to their parents. In order to marry most couples would need to accumulate a savings fund which they could use to finance the creation of their new household, since it was uncommon for a married couple to live in their parents’ household. This meant that if real incomes rose (assuming this happens as a result of economic growth) that couples would be able to afford to marry and establish a joint household at a younger age, hence reducing the FAFM and leading to an increase in fertility. We have already seen that the FAFM did in fact fall over the period of 1680 to 1820, perhaps a large part of this can be explained by economic growth which led to higher incomes.

Higher real incomes which came about from economic growth may be the driving force behind the increase in nourishment which allowed females (and males) to eat better which increased the chance of them having a live birth instead of a stillbirth. An increase in live births would have meant a higher fertility rate thus linking economic growth to fertility.

Moving on, we will explore how the fertility rate affects economic growth: A higher fertility rate would lead to a rise in the population, ceteris paribus, which would mean a rightward shift of the supply curve for labour. This rightward shift would mean a lower real wage would be paid.

For this to be the case we need to assume that mortality held constant (or fell) here, otherwise this could offset the increase in fertility and lead to zero population growth resulting in a fairly constant wage rate.

A lower wage would mean that firms would likely hire more workers at the expense of investing in capital, due to the differences in their costs – it would be cheaper to use labour in the production process than having to rent more costly capital. We would also assume that a lower wage would mean that the age of marriage would rise, as couples would be less able to afford the expense of marriage and creation of a new household. This process is known as the Malthusian preventive check, whereby low incomes resulted in lower fertility – as people married later, or not at all – lowering the population (ceteris paribus) and causing incomes to rise back to the equilibrium. Whilst the Malthusian preventive check held in the 17th Century it would have kept incomes high (comparative to the rest of the world) and led to a higher standard of living, along with an increase in savings (further helped by young people saving for marriage) which could be used to finance investment. Thus in the 17th Century higher incomes helped pave the way for capital investment.

But the data shows us that the fertility rate doesn’t actually fall in the 18th Century, like Malthus would expect, despite a lower income. One argument which explains this contradiction is that during the 18th Century the agricultural revolution resulted in the price of foodstuffs falling dramatically, so that people spent a lower relative share of their incomes on food whilst still potentially being able to increase the amount they ate. This led to a breakdown of the Malthusian preventive check, allowing fertility to rise whilst incomes fell. Furthermore, this could explain how nourishment increased (leading to higher fertility from lower stillbirths) despite the fact that we would expect lower wages from a higher population. Because they ended up spending a smaller share of their income on food it meant they had a larger share to spend on consumer goods, which could have led to an increase in aggregate demand thus fuelling industrial production. We would assume that this would mean a higher demand for labour (as labour is a derived demand) thus increasing wages and fuelling further economic growth. However, if wages grew too high then it would cause an incentive for firms to invest in capital, not that this would necessarily be a bad thing for workers as demand may increase for them to augment capital. If this were the case then incomes would remain high leading to higher standards of living and high fertility, as we can see from the data.

To conclude, the links between fertility and economic growth work both ways – high levels of fertility led to lower real wages in the 17th Century which meant that firms could achieve growth by utilising cheap labour. This link began to break down by the 18th/19th century as a result of the agricultural revolution which meant that relative income spending on food fell, allowing consumers to spend more money on consumer goods produced by industry, thus leading to economic growth. This high economic growth would then follow through into high fertility as the female age of first marriage would fall as would the number of stillbirths, both leading to higher fertility.

Bibliography

Source 1 – CBR and CDR graph, page 66 – E.A. Wrigley: “British population during the long eighteenth century, 1680-1840” in Floud and Johnson, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (volume 1, 2008 edition).

Source 2 – Table 3.4, page 73 – E.A. Wrigley: “British population during the long eighteenth century, 1680-1840” in Floud and Johnson, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (volume 1, 2008 edition).

Source 3 – Figure 3.4, page 72 – E.A. Wrigley: “British population during the long eighteenth century, 1680-1840” in Floud and Johnson, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (volume 1, 2008 edition).

Source 4 – Table 3.2, page 70 – E.A. Wrigley: “British population during the long eighteenth century, 1680-1840” in Floud and Johnson, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (volume 1, 2008 edition).

Source 5 – quote on page 219 – King and Timmins: Making sense of the Industrial Revolution, English Economy and Society 1700-1850