1.a) “The use of data from national accounts in measuring inequality presents many difficulties”. Explain. (readings 4-6)

- b) Explain the difficulties involved in setting a local poverty line, within a country (reading 2 is useful here but also lectures) .

- c) The use of the ‘dollar a day’ poverty line is very popular in everyday discussion of the number of poor across the world. Explain the rationale for the use of this measure. (reading 3)

Inequality is the difference between the incomes of the rich and the poor and there are a number of different measures to see how inequality has been changing over time and between countries. National accounts do not provide any data on how income, consumption or wealth is distributed across households [OECD] instead they provide overall income for the country, and dividing this by the population gives us the average income of the nation. Instead we need to use household survey data to give us a measure of inequality. Such surveys are not consistent across countries and therefore make international comparisons of inequality difficult. To overcome these issues, and allow more precise measures of international inequality, we might consider aggregating the national accounts data with the survey data. Unfortunately, this is a very difficult task, and may cause more issues than it solves. One such issue is that in survey data, households who own their home when asked their income may not include an imputed value of their rent, but this is done when we construct the national accounts. Deaton believes that this factor alone is responsible for explaining a large majority in the difference between national income as given by the national accounts versus the household surveys.

Sala-i-Martin attempts to create a world distribution of income, and use this to measure how world inequality has changed over the period 1970-2000, all measures of inequality show that global inequality declined over this period; his method is heavily critiqued by Milanovic. The problem with a lot of studies on global inequality is that they take a population-weighted figure of national income, which thereby assumes that all people within a country have the same level of inequality, and so the studies are missing a large chunk of the picture. By this method, most studies find that global inequality is rising. Yet, Sala-i-Martin overcomes this by using household studies to create individual country income distributions and finds that inequality is actually decreasing. Unfortunately his study isn’t perfect, as he omits a number of countries due to lack of data and includes some countries with only one data source and then either estimates the income distribution from this one source, to span a 30-year period (effectively assuming inequality hasn’t changed in this country over the time period, thus biasing the overall result), or is unable to even estimate the income distribution and so assumes that it is simply the average – the same failure that other authors make. Milanovic suggests that Sala-i-Martin’s study is even more pernicious, in that the data sources he omits aren’t consistent: he includes some countries with only one data point yet omit several former-USSR countries (including Russia) which have many more data points. Milanov believes that these former-USSR countries, are the ones that have seen inequality rising the most over the studied period, implying that Sala-i-Martin may have omitted them to bias his results. Taking the Gini coefficient, as our measure of inequality, Sala-i-Martin reports that it fell by 4% between 1970 and 2000. On the other hand, taking Milanovic’s criticisms into account, he believes we would need to add 1.5 Gini points to observations after 1990, thus suggesting that the Gini has been stable over the period. Even if we accept this criticism, it differs from UNDP studies which find inequality rising.

In order to set a local poverty line we need to be able to first define what poverty means and then find a useful metric to measure it with. In a broad sense we can think of as poverty as the lack of enough income to be able to purchase a basic standard of living. In one sense any measure of poverty is illusionary in that we classify people living marginally below a fixed value (the poverty line) as living in poverty and in need of assistance, whilst those living marginally above the poverty line will tend to be ignored by such policy. But in another sense, we want to be able to measure levels of poverty so that policymakers can work to alleviate the number of people who are living below what a society deems to be a basic standard of living.

One way we can measure this is using a cost of basic needs basket, which creates a basket of what is considered the minimum amount of food needed to survive. We use food as our primary commodity in this basket because it accounts for almost ¾ of a poor person’s budget in the lowest-income countries. This presents us with many issues; firstly we need to define the minimum, this is often done in terms of calories and is usually set at a calorie intake of between 2000 and 2100 calories; secondly when we create this basket of 2000 calories, how do we decide what food items to include. Stigler points out that calories can come from a wide range of food sources, and he himself creates such a basket to give a scientifically nutritious diet at the minimum cost but highlights the blandness of the diet. Therefore any cost of basic needs measure will have normative judgements imposed about the number of calories included, the types of food included and the quality of such food. Rowntree, in his 1901 survey of poverty defined it based on a cost of basic needs basket and was ridiculed for this in a Parliamentary enquiry by Ernest Bevin who sourced the items in the basket to show Parliament the poor quality and meagreness of a diet: questioning whether somebody who lived on such a diet could be classified as being above a state of poverty. Our final issue with this method is that it focuses on food, and doesn’t account for the fact that to lead a basic life, commodities other than food are necessary, such as medicine, shelter and clothing.

On this point Sen draws our attention to the point that a basic standard of living shouldn’t just include commodities. Whilst a high income may be desired in life, it would be worthless if an individual’s health was poor (assuming the income couldn’t be used to mitigate this). Furthermore some may believe that individuals also need a sense of freedom to pursue different activities, education so that they can lead a fruitful life and political rights so that they feel secure and protected. Hence we mustn’t get fixated on measures of poverty which solely focus on attaining a certain level of commodity possession: whilst important, it isn’t the full picture.

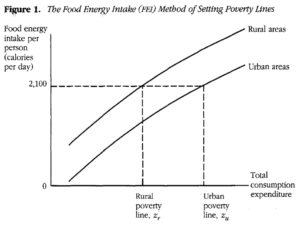

As we have seen, the above method is fraught with difficulties in its construction. Instead, some economists propose that we use the food-energy intake method, which looks at an individual’s consumption level and see what income they need to afford a certain level of calories.

The above graph shows this for rural dwellers and urbanites. We can see that the rural poverty line is lower than the urban poverty line which would imply that poverty will be higher in urban than rural areas; despite many studies showing this isn’t the case. Whilst we would expect the urban poverty line to perhaps be slightly above the rural poverty line because congestion charges generally mean food is more expensive in urban areas, this should be offset by the fact that urbanites require less calories than rural dwellers due to the sedentary lives they lead. The reason this anomaly exists is because rural individuals are more likely to spend a higher percentage of their income on food – as they require a greater number of calories, to conduct their strenuous activities, than do urbanites – and so to feed them 2,100 calories would require less money than to feed an urbanite 2,100 calories who will be spending more of his income on other things. Ravallian and Bidani also point out that urbanites have more advanced food desires, resulting in more expensive food; that congestion costs may mean that food is more expensive in urban areas; and because non-food goods tend to be relatively cheaper than food goods in urban areas versus rural areas, and hence urban consumers may decide to consume more non-food goods due to the differences in relative prices. In its defence this method does therefore allow for the inclusions of Sen’s notion of poverty (see below), in that urbanites are given enough income to fund a living commensurate with their neighbours who share similar food tastes.

We can see this anomaly in another way if we consider a rural dweller, living just above the FEI rural poverty line, who decides to move to the city. The fact he has moved means his expected income must be higher in the urban area, and if we assume that his welfare increase is less than the difference between the urban and rural poverty line, then it turns out that the migration – which has made the individual better off – has increased the nation’s poverty figures. Hence economic development which arises, or leads, to urban expansion, with its citizens becoming better off can actually, statistically see a rise in poverty figures; this would suggest that such figures should be evaluated with this in mind.

So far our analyse has stuck to levels of absolute poverty: it is defined based on a numerical value than is independent of the income distribution in the rest of the economy. Other development economists believe we should take into account relative poverty, which could be measured as the number of people living on an income below some percentage of the mean or median income of a country. But this may cause issues, as Ravallion and Bidani point out that the poverty rate in the US and Indonesia are both around 15%, yet one would be “loath” to assume that absolute poverty was the same in both countries. Therefore, whilst relative poverty may be a useful metric in resolving income tensions within a country, it may distort the picture if we attempt to make international comparisons on such a measure.

Economists such as Ravallion believe that absolute poverty measures should be consistent; that is they should be the same no matter where an individual lives. Hence if two individuals live on opposite sides of the country but consume the same basket of goods (which is deemed as insufficient) then both individuals should be considered as living in poverty.

Sen believes that even if an individual has an income exceeding that of the absolute poverty level, he may feel isolated from society if his income is not as great as his peers. This would imply that poverty shouldn’t be seen as consistent across geography, and should instead depend upon where an individual lives. Unfortunately this is seen as a luxury by some, and others contend that we should focus on ensuring that everybody lives above what is defined as absolute poverty, before we ensure that everybody has enough incomes for 2 TVs to match their neighbours.

In summary, we have shown that there are many difficulties in creating a local poverty line, and the measure we use is important: the number of urbanites living in poverty in Indonesia according to the food-energy intake method is 16.8% whereas according to the cost-of-basic needs method it is 10.7%: a substantial difference. Many measures are used and each takes a different normative judgement of what it is to be living in poverty. It is impossible to say which method is unequivocally “right”, or which is “wrong”; rather than give up hope that we can ever measure poverty, we should instead refer to the range of measures we do have as giving us insight into the number of people living in poverty and inform the public, and policymakers so they can try to improve the lot of the poorest in our society.

The dollar a day measure of poverty is very popular for its ability to grab headlines and the attention of the public with a measure of poverty that almost everyone can grasp. The first goal of the Millennium Development Goals was to “reduce by half, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day”. It may therefore be seen as a useful tool of development economists in reducing poverty if it is easily understood by policymakers and the public alike.

In principle it takes US$1 and converts it in to local exchange rates around the world, and then a count of the number of people living below this level is taken and aggregate across the world giving us the total number of poor. In fact, the dollar a day measure is no longer even a dollar a day, but is $1.25 in 2005 prices as a result of inflation and as a general increase in the poverty line, but due to its ease we stick with the name “dollar a day”.

It was initially decided that a dollar a day would be the poverty line, mainly because this was the US value of the poverty line in India, a country with one of the highest poverty rates. In recent years an average of the poorest countries’ poverty line is taken to give us our $1.25 value. This means that if the poorest countries in the world increase their poverty line, then the global poverty line will also increase. Thus this may lead to more people being put into the class of “poverty” without any deterioration in their incomes and highlights one of the issues with this measure. Instead, as Deaton suggests, we should have a fixed poverty line so that we can successfully evaluate how many people are being taken out of poverty (if at all) over time.

A further issue with this measure is how we convert US$1 into local currencies. This is done through the PPP exchange rates, rather than official exchange rates, due to the Balassa-Samuelson effect which results in exchange rates for developing countries being undervalued compared to developed countries (the Penn effect). However Deaton has great issues with PPP, as the reindexing of the base year has serious effects on the number classified as poor: half a billion people were moved into poverty by the 2005 PPP adjustment. Thus it is difficult to put much faith in poverty estimates if they are liable to such change, and are dependent on this index.