Describe the macro-level externalities of high fertility in poor countries

The most important macro externality that high fertility can have is its effect on economic development. If high fertility leads to more rapid economic growth and development then we may consider the externality positive, if not we would say it is negative. This works if we consider the mortality rate to be below high fertility, such that high fertility means high population growth.

There are various reasons and models to believe that high fertility does indeed promote growth, but many others which refute this and argue that high fertility inhibits growth. The Solow model is one such model which would imply that high fertility (even if we have high mortality, we have still spent investment capital on educating and training these workers, regardless of whether they survive to realise this investment) reduces economic growth, because if there are more people then we need to train them and provide them with capital which depletes the fixed level of investment spending. If we are spending more investment money on equipping workers with basic tools, then we have less money to invest in better tools which may enhance economic growth and permit the economy to emerge from a poverty trap; for example, by allowing it to move into the manufacturing sector, with higher incomes than the more basic agricultural industries. Similarly, evidence from Britain’s Industrial Revolution suggests that high population growth is bad for economic development, because it lowers wages and thus disincentives inventors from creating labour-augmenting technology which propels the economy. However, it could be argued that when developed countries already exist which are able to produce such technology, it is irrelevant to a developing country which can just copy this technology, and has no need to develop its own.

Conversely, economists such as Simon and Boserup would argue that high fertility leading to high population growth can be good for economic growth, and therefore gives us a positive externality from high population. Simon argues that the more people we have, the more chance we have of finding a genius who can develop new technologies to propel the economy. Boserup believes that having more people means there is a lower per capita cost of infrastructure, which should increase the provision of such infrastructure which is likely to increase economic activity. Furthermore, a greater population will mean a larger market and hence greater potential for increasing returns to scale. Whilst this could be countered by the growing importance of international trade making the market almost infinite, it is still the case that there are barriers to trade, particularly for poor countries. It is easier to trade domestically due to international transport costs, trade barriers, and the need for a homogeneous market to sell standardised goods to. This means that increasing returns to scale arising from a greater population is still an important consideration.

Whilst both views have flaws, they are quite convincing, yet to summarise the view of most mainstream economists, it is widely believed that high population growth is detrimental to economic growth. Therefore we could extrapolate this to argue that high fertility is likely to have a negative coefficient attached to the macro externality.

Considering other macro-externalities, we turn to research conducted by Lee and Miller who try to quantify macro-externalities to childbearing, which include the public costs associated with education, healthcare and pensions, which would be negative. Offset by the future tax that the children will provide, which is a positive externality, alongside the cost sharing of public goods and social infrastructure (similar to Boserup). Moreover, a large population aids the country in its military aims in two senses, firstly there is a greater population which can be used to fight any future wars, and secondly, there is a greater population to pay taxes for the (mostly) fixed costs associated with military spending. The authors believe that these “uniformly positive externalities arising from public good expenditures should not be dismissed lightly”.

They also consider the pecuniary externality of the effect on wages. They believe that high fertility will mean a future rightward shift of the labour supply curve, which will lower wages: they associate high fertility with lower future wages which will make people worse off. Whilst this makes sense in a partial-equilibrium model, if we consider a general-equilibrium model it might seem less likely. After all, this increased population will demand goods and services from the private sector, and so will increase demand which ought to shift the labour demand curve rightwards (resulting from derived demand for labour) by at least as much, if not more due to rising aspirations. Lee and Miller ignore this externality regardless, because they see it as pecuniary and only consider technical externalities, but it could be contested that this pecuniary externality need not be negative – as they assume – and under the right conditions (largely arising from public intervention and provision of public goods) this could be positive.

They consider the most basic form of externality one in which access to the commons results in depletion. If parents have free access to an area in which they can collect water, fuel and food then they don’t fully bear the costs from having greater children, and thus may increase their fertility. As a result we may see the environment deteriorate – deforestation, air and water pollution and overkilling of rare species of animals – as a result of high fertility levels.

Examining their results we find that despite the positive externalities which do exist, the overwhelming evidence for poor countries suggests that macro-level externalities are negative from high fertility, this is largely due to the claim that citizens in poor countries have on commodities such as minerals and oil (a greater population means that more people require government funds resulting from the sale of these commodities). Hence we must conclude that despite positive externalities the size of the negative externalities, on a macro level, outweigh these and result in an overall negative externality to high fertility for poor countries (but the results are reversed for richer countries), particularly as the study largely omits environmental concerns, mainly due to a lack of information on the size of the damage a high population inflicts on the environment, and in their being limitations in how we can attach an economic cost to such damage.

- Explain why household micro-externalities associated with fertility behaviour create a dissonance between the socially optimal level of childbearing and the privately optimal level of childbearing.

We have already seen that at the macro level, the socially optimal level of child-bearing tends to be lower than the privately optimal level of childbearing in poor countries: that is, people tend to have more children than society would desire, given the negative externality they inflict on society as a whole.

For this to occur, it must be the case that individuals do not fully face the costs that are inflicted on society, whilst they still receive many of the benefits from children, such as their role as consumer goods along with their benefits as economic goods, and hence don’t include these in their fertility decisions. Furthermore, individuals have an issue of imperfect information: they can’t possibly know the full costs and benefits associated with having children, and this can lead to overproduction of children as we will discover.

Firstly, in many developing countries there is a cultural phenomenon of extended families looking after children. In parts of West Africa up to half the children have been found to be living with kin other than their parents at any given time (Dasgupta). Furthermore, Iyer finds that in Ramanagaram, India nearly 77% of surveyed women had extended family helping with child care. This means that parents don’t face the full costs of childcare, as they no longer bear this themselves – either through the opportunity cost of not working to look after the child(s) themselves, or the economic cost of having to pay a market-provided child-minder. Microeconomic theory tells us that when an individual doesn’t fully face the costs of an economic decision (which provides them with positive private utility) then they will demand more than is socially optimal. We can consider this below, where we assume that the marginal private benefit of having more children is equal to the marginal social benefit (a restriction we will relax later) but the marginal private cost is lower than the marginal social cost.

[Figure Unavailable]

As we observe, the result is overproduction in society’s sense because people would choose the fertility decision Q2 and produce more children than is socially desired, which is the level of Q1. This result is exacerbated by the fact that the government tends to provide services such as education and healthcare freely, which would mean that the marginal private cost to having more children is even lower than the marginal social cost shown above. The immediate policy implications of this might imply that we should encourage governments to charge (perhaps only a fraction) for provision of public goods, but this has detrimental income distribution effects, and there may be other ways to ameliorate the situation which don’t lead to immediately greater poverty levels (although these may fall over time if they are successful in reducing the population level).

Whilst this would suggest that the cultural phenomenon of large extended families living together, or the system of fosterage, is detrimental it can have other positive effects. Hajnal observes that having the extended family co-resident can result in lower levels of fertility due to a lack of privacy to stimulate sexual activity, and because there is greater monitoring of sexual intercourse happening at specified times (perhaps due to religious observance). Furthermore, the social interaction effect of having other women in a household can inform a parent of the costs of children as well as unknown contraceptive measures.

Secondly, as we have explored in part (a) it is likely that the marginal private benefit of having children is greater than the marginal social benefit. This is because parents can enjoy the services which children provide, including personal satisfaction and happiness, along with economic benefits as investment goods, a form of insurance and as production goods. This last issue, of children as production goods, if true, is likely to mean large marginal private benefits from having children, because children can be used to help the family produce goods and are particularly important in collecting firewood (boys) and water (girls) (Iyer). A consequence of the MPB exceeding the MSB is that there is an even greater demand for children than considered above. However, if an extended family is present then this may well offset the need for children as production goods: Kanbargi and Kulkarni find that if grandparents are present in a household then they take over many of the productive roles of children, for example looking after younger siblings.

Thirdly, we haven’t considered the Marshallian atmospheric externalities which arise because of social norms and the spill-over effect that an individual’s decision has on society. Evidence from the field of sociology shows us that people tend to emulate the decisions of their neighbours and peers, as a result of the desire to conform – people don’t like the uncertainty attached with being an outsider – and to maintain a certain social status. Hence one couple’s fertility decisions are likely to affect their neighbours since individuals gain more utility out of a particular course of action because those in their immediate area undergo a particular course of action. This can lead an individual’s fertility decision to have a knock-on effect, resulting in high levels of fertility across society.

- Do reproductive externalities cause coordination failures that prevent fertility rates from falling rapidly in poor countries?

We have already explored many of the reproductive externalities associated with high fertility. We have seen that the culture of fosterage and having extended families co-resident can lead to more children being demanded than is socially optimal, although there are factors offsetting this. Access to the commons may mean that it is privately beneficial to have more children, who can then collect firewood, food and water from the commons. This can lead to Lloyd’s tragedy of the commons where it is socially optimal to reduce the number of children who are using the commons (and who require sustenance themselves), but it is not privately beneficial to do so unless other families make the same decision.

Remembering that an externality arises when the true cost isn’t reflected in market prices it must be the case that an externality exists because many household decisions are made by the man of the house, who doesn’t bear the costs of child-birth nor child-bearing which the woman faces. This shows that the decision-maker (man) is going to over-demand children, because he receives many of the benefits of having a child, but doesn’t face all of the costs. To overcome this issue we would need to increase the economic and social power of women; one way in which this can be done is through increasing the educational attainment of women along with better access to female labour markets. This will then allow women access to work in higher income jobs which gives them more bargaining power in the relationship – as they are bringing a valuable source of income into the household, as well as more outside options which increase bargaining power through the threat of divorce.

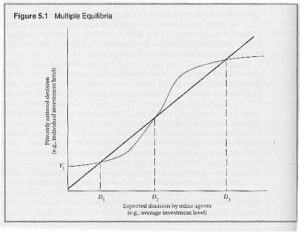

The negative reproductive externalities thus far discussed, such as state provided education and healthcare, fosterage, the gender imbalance, Marshallian atmospheric externalities and access to commons are all factors that are likely to prevent fertility rates from falling rapidly because there is no incentive to reduce fertility decisions by oneself. It can therefore be seen as a co-ordination failure, because if people could jointly agree to reduce their fertility behaviour then they would all jointly benefit – after all, the social optimal is for fertility to fall – but there is a credibility issue, as one family isn’t going to reduce their fertility behaviour unless they can be sure that others will follow suit (Kohler). This is due to social issues, such as wishing to conform to their peers and maintain a certain social status (Dasgupta) and because reducing family size by oneself may mean a loss of benefits – such as the ability to take from the commons – which could be exploited by others who do have large families. As a result we have a situation in which we have multiple equilibrium, as shown below, whereby we start at D3 (the high fertility equilibrium) but would rather be at D1 (the low fertility equilibrium) which is socially optimal.

Dasgupta suggests that one way in which we can overcome the coordination failure and move from D3 to D1 is through government intervention and the introduction of a tax on children, or a subsidy for having fewer children. Yet it may be possible to affect the social relations instead, rather than resorting to government intervention in the market. This can be achieved through other means, such as increasing education which often leads women to want fewer children (because they have greater opportunity costs for their time and have greater aspirations). This will then have a domino effect, because these social “deviants” (so-called because they go against the grain in wanting smaller families) will interact with others who are likely to then change their fertility decisions as the majority tend towards this socially deviant minority in order to reduce differences (Montgommery and Casterline). However, this mechanism will only work so long as the educated women still interact with other non-educated women such that the social interaction isn’t confined to one demographic only. Furthermore, this type of social spill-over is normally confined to the same gender (Bongaarts and Watkins), and as already discussed, men have a disproportionate role in the decision-making of fertility decisions, so action needs to be taken to reduce their fertility decisions.

Another method may be to alter social attitudes through the media, for example through soap operas on TV, and the beliefs espoused in newspapers and magazines.

In summary, reproductive externalities can lead to coordination failures due to cultural and social phenomena which result in individuals wanting to be seen as socially normal, and not deviate from what their neighbours and peers are doing. In a situation of multiple equilibria, this results in an undesirable equilibrium – that of high fertility – being the stable equilibrium, which we can only escape from through the action of social deviants, and through government action which attempts to change what is believed to be the social norm through media and through the mechanisms of the state. Fortunately, Coale finds that once a region has begun a fertility decline it quickly spreads to neighbouring regions with the same language and culture. This is good news for developing countries: if they can overcome the co-ordination failure through social spill-overs then they may be able to quickly reduce their fertility growth, and the negative externalities associated with this.