Reciprocity, a mutual or reciprocal reduction in tariffs, is a key feature of trade agreements between large countries. Explain why reciprocity is a necessary feature for a trade agreement to yield higher welfare to both parties. Can a trade agreement be sustainable (or “self-enforcing”) if it is not characterized by reciprocity?

Following McLaren, let us consider two large countries, A and B which are symmetric both countries produce goods a and b, but A has a comparative advantage in the production of a whilst B has a comparative advantage in the production of b. To placate the domestic industry country A has an incentive to impose a tariff on good b which imposes a terms of trade loss for B and efficiency loses for both countries, whilst B has an incentive to impose a tariff on good a causing a terms of trade loss for A and efficiency losses for both country. We can see these losses below, where we consider the tariff that A places on b:

On the left panel we see the effect of the tariff on b for Country A: the red triangles represent efficiency losses; the left triangle represents the loss to consumer surplus due to the higher price, whilst the right triangle represents the production distortion because A is less efficient at producing b than B is. The green square represents the terms of trade gain to A: by imposing a tariff it has managed to reduced the world price of the good (through lower demand), and so can purchase the good (pre-tariff) more cheaply. On the right panel we can see that the tariff has imposed a complete loss to B: it loses the left triangle (B’) in consumer surplus due to the higher world price caused by less B production of b, it loses the square C in terms of trade loss and the triangle D’ as a production distortion. These losses are known in the literature as the terms-of-trade externality.

Due to our assumption of symmetry, we would see identical but opposite loses/gains for A. This non-cooperative, protection policy is a Nash equilibrium for each country as it maximises domestic social welfare and there is no incentive for the country to change its strategy based on what the other country will optimally do.

On the other hand, if we considered both countries removing the tariff then there would be a Pareto improvement, as both countries would be better off. This is because the terms of trade are defined as the ratio of export to import prices on the world market, exclusive of tariffs, and hence means that reciprocal tariff cuts will not affect terms of trade and so both countries can gain. Thus, this is another Nash equilibrium (NE) which is Pareto superior to the non-cooperative NE. Tower shows that the static Nash equilibrium when considering quotas is complete autarky. The static Nash equilibrium when considering tariffs is either complete autarky or an interior solution.

Hence in order to reach and sustain this superior NE there would need to be some form of punishment if a country deviated, and imposed high tariffs to capture a large TOT gain. This punishment can take the form of a Nash reversion strategy, whereby if a country deviates the other country will revert to protectionist policy (or autarky in the extreme) and both countries will return to the Pareto inefficient NE and so will be worse off. This game theoretical analysis therefore explains why reciprocity is a necessary feature for a trade agreement to yield higher welfare to both parties: without it the Nash equilibrium is protectionist policy with an inefficient outcome.

Bagwell and Staiger (BS) show that when a country has a welfare function which assigns equal weighting to producers, consumers and tariff revenue then our reciprocal trade agreement will be efficient, whilst if there is a political motive (to maximise government revenue from lobbyists) which results in producer surplus being assigned a greater weight then our outcome will be political optimal. BS demonstrate that reciprocity is needed by examining the indifference curves of a country in tariff space:

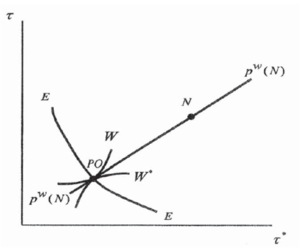

The home country (A) has its indifference curve described by WN which is increasing in utility towards the west, whilst the foreign country (B) has its indifference curve described by W*N which is increasing in utility towards the south. EE gives the contract curve which tells us that Pareto efficient outcomes, which occurs when the two indifference curves are tangent. The current set-up shows an intersection of N (the other intersection is possible, but as it is not Pareto superior, due to the assumption of symmetry and the notion that terms of trade is exclusive of tariffs, the intersection N is more desirable because it permits higher tariff revenue) which is our non-cooperative Nash equilibrium with high tariffs (protectionism). By jointly reducing tariffs (reciprocity) the world price will be unchanged and hence their indifference curves will shift in the direction of increasing utility. The case to the left shows a politically optimal outcome, whereby tariffs aren’t zero, such that producers will lobby the government to maximise the level of these tariffs, but it is Pareto superior to the Nash equilibrium.

To summarise, we have seen that reciprocity is a necessary feature for both countries to see higher welfare, due to the definition of terms of trade, and because of cooperation to reach the Pareto superior Nash equilibrium. Whilst it is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient, as Bagwell and Staiger point out by considering three countries. When this is the case local-price externalities can arise unless we impose the condition of non-discrimination, whereby the lowest tariff offered to a trading partner must be offered to all other trading partners, otherwise local-price externalities will arise, rather than the normal terms-of-trade externality that tariff reductions seek to eliminate. Furthermore, as McLaren points out, if two countries, A and B, engage in a bilateral trade reduction (reciprocity, but without MFN) then one party, A, may be inclined to sign a trade deal with another country, C, for an even greater trade reduction which undermines the benefits that B will experience.

Considering a trade agreement which is not characterised by reciprocity – i.e. one country reduces tariffs whilst another doesn’t – we see that the country which reduces its tariffs (R) will lose tariff revenue and will see a terms of trade loss (the price of the import will rise because demand will rise without the tariff) but will benefit from reduced distortions (an increase in consumer surplus and a reduction in production inefficiency). The other country will benefit from a terms of trade gain and a reduction in inefficiency losses whilst maintaining tariff revenue. If the government weighted producers, consumers and tariff revenue equally in its social welfare function, then it could be possible that this is self-sustaining as a Nash equilibrium so long as the reduction in inefficiently more than offsets the loss in tariff revenue and producer surplus.